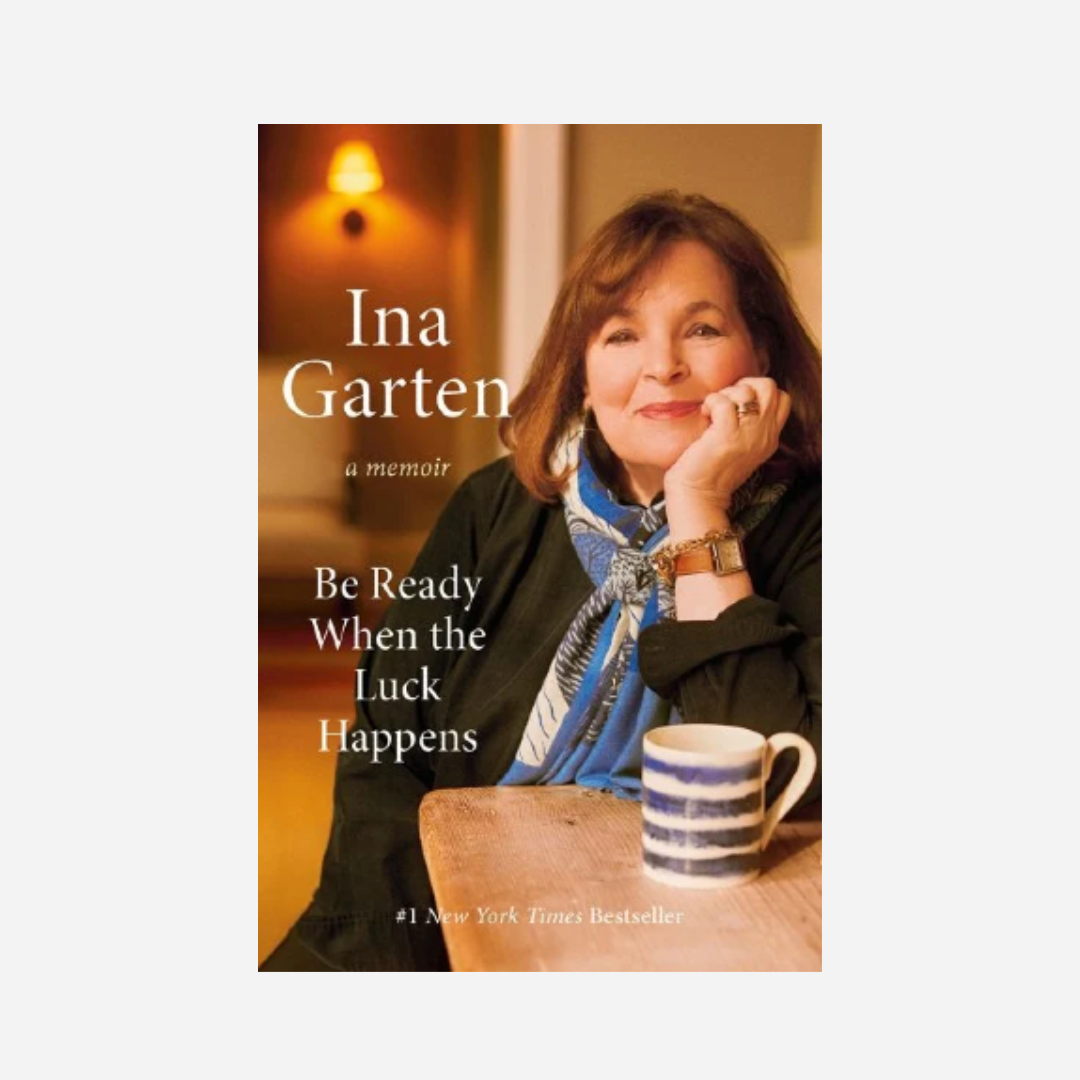

I Regret Almost Everything by Keith McNally

Come for the cocktail party of reading his firsthand accounts of downtown New York, then partake in the feast he offers on how catastrophe forces you to reconsider your life. Dessert will be a humbly delivered lesson in better understanding somebody in your own life who has had a stroke.

First off, I’ll be honest, I picked it up for the glamorous, glittering cocktail party that was going to be McNally’s description of his life as the restaurateur who invented downtown. Also for more of the pugnacious, withering takes on haughty boldface names like the ones he posts on his instagram account. And then because Ruth Reichl, whose memoirs I loved, promised it would take me “deep into the power of literature, art, and theater to expand [my] worldview.”

And finally, because I can’t resist the arc of a life story that begins in a prefab house with linoleum floors in working class Bethnal Green in the East End of London, then moves through an early stint in British theater, ascends to creating a NYC downtown scene that included Odeon, Nell’s and then Balthazar. It eventually lands, as we all know, with a sudden thud 60ish years later back in London with a stroke that leaves him with partial paralysis and impaired speech.

There’s been a lot already said about McNally’s memoir I Regret Almost Everything, yet I was somehow unprepared for the power and the heart of his memoir. The real feast is his surprisingly vulnerable and humble revelations about the pain, depression and aftereffects, both emotional and physical, of his stroke. His shame over his fragility and diminished capabilities, his discouragement dealing with the unfair, Byzantine and also outright scammy medical system. There were ripple effects on his family, on his relationship with his second wife and their two children, and particularly on one of his sons, who found him after he had tried to kill himself.

That’s where all the regrets come in. Most significantly, he regrets his own failures (mostly of neglect or self-absorption) in his marriages and as a father (most painful to read, and daring to admit, was his failure to visit his daughter while she spent time in McLean’s, a psychiatric hospital, for crippling anxiety). There were restaurant failures where he relied more on his intuition than reason. There was a falling out with his brother Brian McNally, also a maestro of downtown New York. He regrets calling James Corden out publicly for rudeness (based on secondhand accounts) and banning him from his restaurant, possibly damaging Corden’s reputation and career. He expresses remorse over having attempted suicide.

It was the stroke, I believe McNally suggests, not any personal or professional accomplishment or failure, that was the major turning point in his life. His stroke occurred in 2016; the memoir was recently published in 2025. The feeling the memoir gives is of being written entirely through the lens of his stroke. If he’d never had the stroke, would he have been able to see his past with such vulnerability and humility? His stroke was the bomb that blew him open in order for him to be able to look at himself, his life and failures, with such piercing clarity.

It could have been drudgery, but what makes reading his honest accounting of his regrets palatable, even while he does so unsparingly, is not only that he offers sympathy for those he hurt, but also because he offers himself some sympathy, too. If only in the form of acknowledging that his mistakes were necessary to get from where he began (geographically, but also emotionally) in Bethnal Green to where he is now.

From the downtown glamour to the emotional grit, McNally‘s memoir offers a lot to partake in. But for those of us who love, or have loved, somebody who has had a stroke we get insight it would be hard to access so acutely anywhere else. McNally puts us inside his darkest thoughts as he recovers. I’ll say this, both my Mother and sister have had strokes — people I obviously know intimately and over time — yet, reading McNally’s memoir has allowed me to understand their worlds in a way that they haven't, or I now realize, most likely can’t. (I was surprised by how much shame he felt (perhaps still feels) over his paralysis and impaired speech.) I hope that it makes me more empathetic and better at loving and caring for them.

McNally’s life story offers a lot to ogle, despair over, exalt in, sympathize with — it even encourages your own deep self-reflection — but in its simplest and most transcendent terms, for me it has been an incredibly useful guide to living with and loving somebody who has had a stroke. That alone is a banquet.

The Crush Letter

The Crush Letter is a weekly newsletter from Dish Stanley on everything life, love & culture. It's a view through the eyes of somebody over 50 who has found that midlife is a lot cooler than they said it would be. If you’d like to take a look at some of our best stories go to Read Us. Want the Dish?

Other stories from The Crush Letter you might enjoy: